By Dr. Curtis Peterson

We are living in an age of unprecedented connection, yet many people feel increasingly alone.

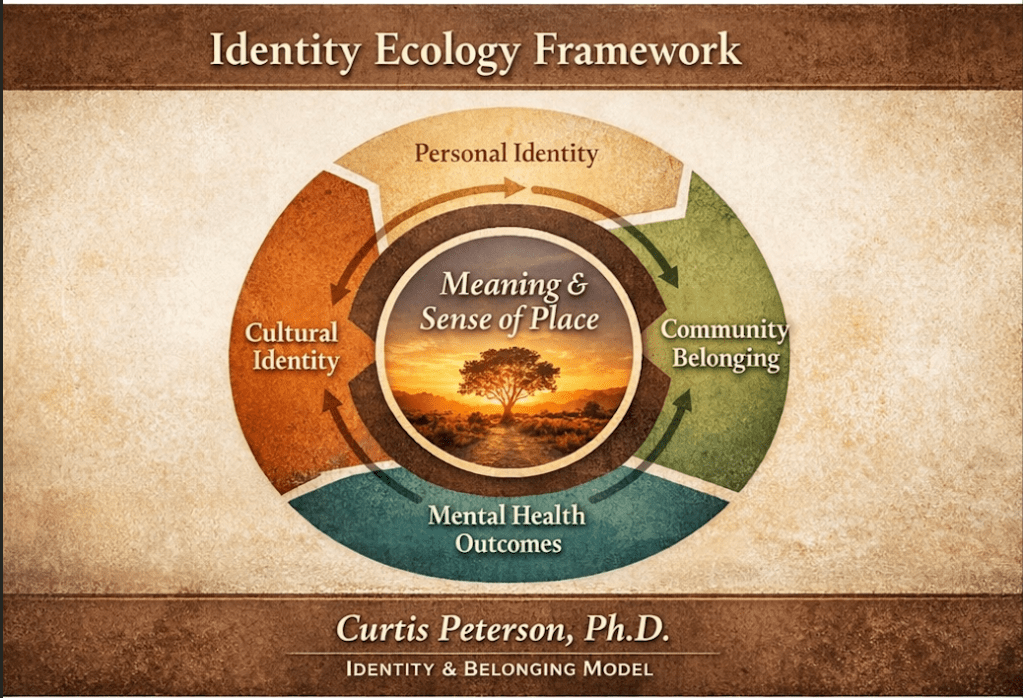

Across classrooms, workplaces, and communities, individuals report a growing sense of disconnection from others, from institutions, and sometimes even from themselves. As a social psychologist who studies identity, belonging, and loneliness, I have come to believe that we are not simply facing a mental health challenge. We are facing a crisis of belonging.

Human beings are fundamentally social. Decades of psychological research have demonstrated that our sense of identity, purpose, and well-being is shaped through relationships and social connection. When those connections weaken or disappear, the consequences extend far beyond temporary feelings of loneliness. Chronic social disconnection has been linked to increased anxiety and depression, diminished physical health, reduced motivation, and a declining sense of meaning in everyday life. Belonging is not a luxury or a secondary need, it is central to human functioning.

Yet belonging is often misunderstood. Many assume it is something that either exists naturally or does not exist at all. In reality, belonging is built through consistent experiences of being seen, valued, and understood within our environments. It grows through everyday interactions—being recognized by name, having one’s ideas acknowledged, or feeling that one’s presence matters within a group. When those experiences accumulate, identity strengthens and well-being improves. When they are absent, isolation can quietly take root.

In my years of teaching and working with students across diverse backgrounds, I have repeatedly heard a similar sentiment: individuals can be surrounded by others and still feel profoundly alone. A student once shared that they attended class, participated in group discussions, and interacted with peers daily, yet felt as though no one truly knew them. Their experience is far from unique. Many people function within social systems schools, workplaces, even families without experiencing a genuine sense of belonging. Over time, this absence can erode confidence, motivation, and connection to others.

This pattern extends beyond educational settings. In modern workplaces, individuals may collaborate with colleagues regularly while feeling interchangeable or unseen. In communities shaped increasingly by digital interaction, people may communicate constantly yet experience limited meaningful connection. We are more technologically connected than at any point in human history, but meaningful social connection requires more than proximity or communication it requires recognition, mutual engagement, and shared understanding.

Like many educators and professionals, I have also observed how easily periods of disconnection can emerge in our own lives. Responsibilities, life transitions, and external pressures can gradually narrow our social worlds. Often, this occurs so subtly that we do not recognize the shift until a sense of isolation has already taken hold. These experiences reinforce what social psychology has long suggested: belonging is not static. It must be actively maintained and, at times, intentionally rebuilt.

Rebuilding belonging does not require dramatic transformation. It often begins with small, deliberate actions. Reaching out to colleagues, engaging in meaningful conversation, participating in shared activities, or creating spaces where others feel seen and heard can gradually restore connection. Belonging is reciprocal; we do not only seek it for ourselves, we help create it for others through our presence and attention. Even modest efforts to strengthen connection can have measurable effects on well-being and life satisfaction.

Educational institutions, workplaces, and communities play a critical role in this process. When environments foster inclusion, respect, and meaningful interaction, individuals are more likely to experience psychological safety and engagement. When those elements are absent, even highly capable and accomplished individuals can experience profound isolation. Understanding the psychology of belonging therefore has implications not only for personal well-being, but also for organizational effectiveness and community health.

We are living through a period of rapid social and cultural change that has altered how people form and maintain relationships. These shifts can make belonging more difficult to sustain, but they also create an opportunity to reconsider how we build connection in modern life. By becoming more intentional about fostering identity, community, and mutual recognition, individuals and institutions can begin to address one of the most pressing psychological challenges of our time.

Belonging is not reserved for a fortunate few. It is a fundamental human need and a shared responsibility. Rebuilding it within ourselves, our classrooms, our workplaces, and our communities may be one of the most meaningful steps we can take toward improving both individual and collective well-being.

Leave a comment