By: Dr. Curtis Peterson

Addiction is a complex and multifaceted condition influenced by various biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Understanding relapse—defined as a return to substance use after a period of abstinence—requires a nuanced examination of the different models that attempt to explain the causes and treatment of addiction. This chapter explores major theoretical models of addiction, integrating empirical research and clinical insights to offer a comprehensive view of relapse prevention within a biopsychosocial framework.

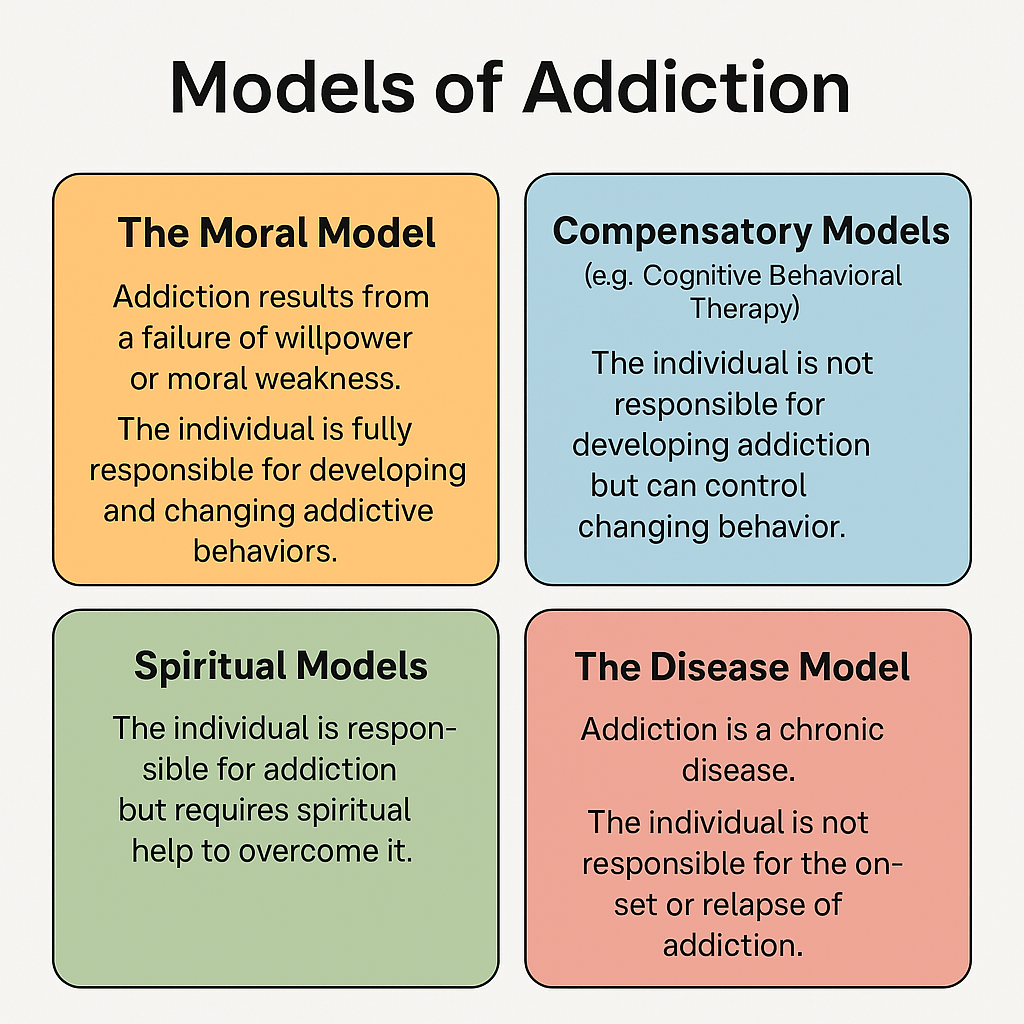

Theoretical Models of Addiction

1. The Moral Model

The Moral Model posits that addiction results from a failure of willpower, moral weakness, or character flaws. Within this framework, individuals are deemed fully responsible for both developing and changing their addictive behaviors (Heather, 2017). Relapse, in this context, is interpreted as a moral failing or lack of personal discipline. This model has historically underpinned punitive approaches to addiction but has largely fallen out of favor due to its stigmatizing and ineffective nature (Saitz, 2014).

2. Compensatory Models (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy)

In Compensatory Models, individuals are not seen as responsible for developing addiction but are considered capable of change. This category includes approaches like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which conceptualize relapse as a temporary lapse or error in judgment rather than a moral failing (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005). The emphasis is on enhancing self-awareness, coping mechanisms, and restructuring maladaptive thought patterns.

3. Spiritual Models

Spiritual Models of addiction, exemplified by 12-Step Programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), hold that individuals are responsible for their addiction but require spiritual assistance to overcome it. Relapse in these models may be interpreted as a loss of spiritual connection or “sin” and recovery as a process of restoring alignment with a higher power (White, 2014). These models have shown effectiveness for individuals with strong spiritual or religious foundations (Tonigan, Miller, & Schermer, 2002).

4. The Disease Model

The Disease Model views addiction as a chronic, relapsing brain disorder. Individuals are not considered responsible for the onset or continuation of the condition, and relapse is seen as a symptom of the disease (Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016). Medical professionals often support this model, which has led to increased acceptance of pharmacological and clinical interventions.

Integrated Treatment Approaches

While this course centers on the Compensatory Model, the usefulness of the other frameworks should not be dismissed. Depending on the client’s beliefs, integrating spiritual models or biological understandings may enhance the effectiveness of treatment. This flexibility aligns with a person-centered approach that respects individual differences and worldviews (Prochaska & Norcross, 2018).

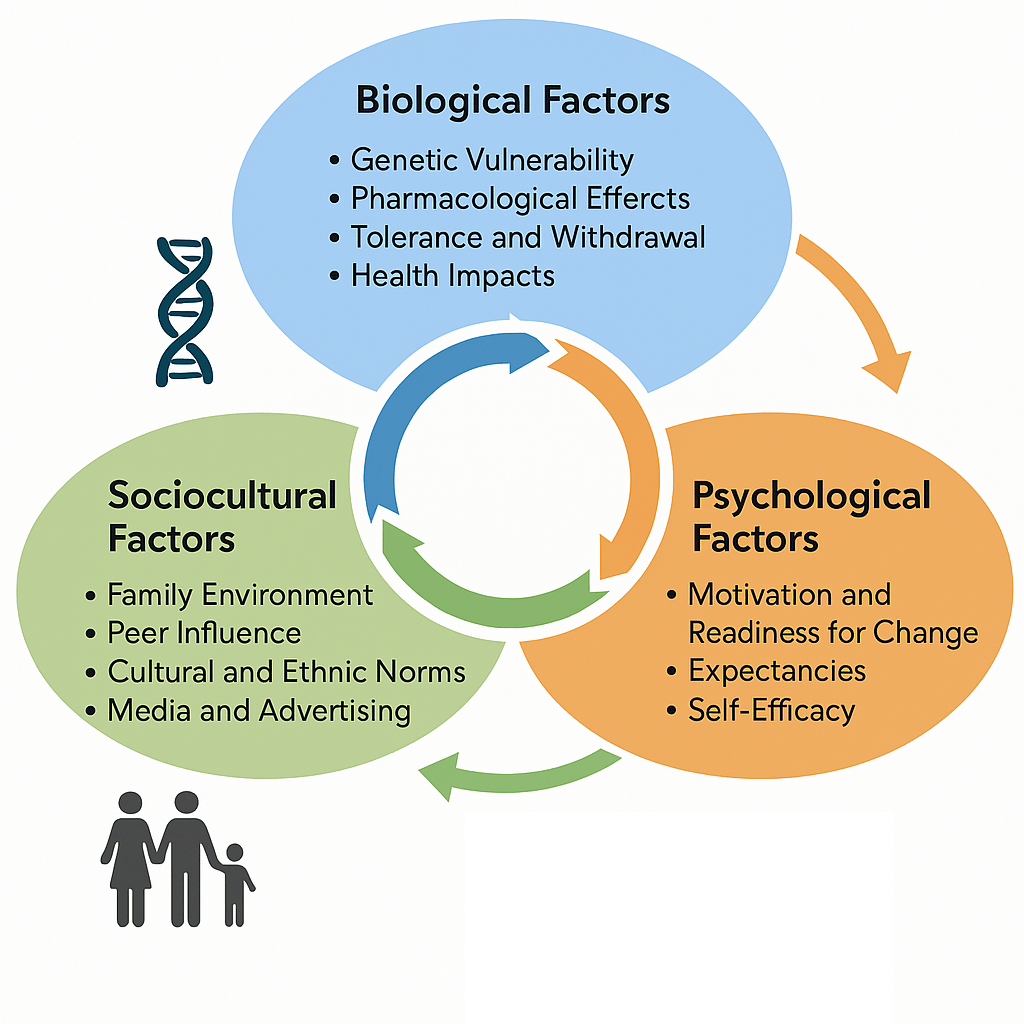

The Biopsychosocial Model of Relapse Prevention

The biopsychosocial model posits that relapse is influenced by an interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Effective treatment requires addressing each of these domains to reduce the risk of recurrence and support sustained recovery (Engel, 1977; McLellan et al., 2000).

Biological Factors

- Genetic Vulnerability: Family history is a significant risk factor; heritability estimates for substance use disorders range from 40–60% (Goldman, Oroszi, & Ducci, 2005).

- Pharmacological Effects: Substances like alcohol interact with neurotransmitter systems (e.g., GABA, dopamine) and can provide temporary analgesia or euphoria, reinforcing continued use (Koob & Le Moal, 2008).

- Tolerance and Withdrawal: With repeated use, the body adapts, necessitating increased doses to achieve the same effect. Withdrawal symptoms, often both physical and psychological, can be severe, contributing to the cycle of dependence (Kosten & O’Connor, 2003).

- Health Impacts: Chronic use is linked to liver disease, cardiovascular problems, neurological impairments, and other medical conditions (Rehm et al., 2009).

Psychological Factors

- Motivation and Readiness for Change: The Transtheoretical Model outlines stages from precontemplation to maintenance, each requiring tailored interventions (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

- Expectancies: Beliefs about the positive effects of substances can override negative consequences, reinforcing use (Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001).

- Self-Efficacy: Confidence in one’s ability to resist cravings is a critical predictor of success (Bandura, 1997).

- Attributional Style: Attributing use to stress or social context can mask underlying psychological drivers and delay intervention.

- Impulsivity and Sensation-Seeking: Linked to childhood trauma and high Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) scores, these traits increase vulnerability to substance misuse (Anda et al., 2006).

- Negative Affect and Coping Deficits: Chronic emotional distress and poor problem-solving abilities significantly increase the risk of relapse (Zvolensky et al., 2006).

Sociocultural Factors

- Family Environment: Parental or sibling substance use normalizes addictive behaviors. Conversely, overprotectiveness without education can leave youth unprepared for exposure (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992).

- Peer Influence: While adolescents are susceptible, research indicates that adults, especially in social or work settings, also face peer pressure to use substances (Lamis, Malone, & Jahn, 2014).

- Cultural and Ethnic Norms: Substance use norms vary widely across cultures. Understanding an individual’s cultural background is vital for effective treatment (Caetano, Clark, & Tam, 1998).

- Media and Advertising: Marketing often glamorizes substance use, shaping public perceptions and expectations (Grube & Waiters, 2005).

The Reality of Relapse Without Treatment

Studies have consistently shown that the absence of structured support drastically lowers the chances of sustained recovery. Approximately 40% of individuals relapse within three months of quitting without formal intervention, and only about 25–30% maintain abstinence after one year (McLellan et al., 2000; Moos & Moos, 2006).

While self-initiated recovery is possible, long-term success is significantly more likely when individuals engage in comprehensive treatment programs that include behavioral therapy, social support, skill development, and accountability (NIDA, 2018).

Conclusion

Relapse is not a singular event but a process influenced by a wide range of interdependent factors. Understanding addiction through multiple lenses—including moral, cognitive, spiritual, and biological—allows for more inclusive and effective interventions. The biopsychosocial model provides a holistic framework that can guide practitioners in tailoring relapse prevention strategies to the unique needs of each individual.

(YouTube video used in lecture to introduce the diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorder.)

References

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Caetano, R., Clark, C. L., & Tam, T. (1998). Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities: Theory and research. Alcohol Health and Research World, 22(4), 233–241.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136.

Goldman, D., Oroszi, G., & Ducci, F. (2005). The genetics of addictions: Uncovering the genes. Nature Reviews Genetics, 6(7), 521–532.

Grube, J. W., & Waiters, E. (2005). Alcohol in the media: Content and effects on drinking beliefs and behaviors among youth. Adolescent Medicine Clinics, 16(2), 327–343.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 64–105.

Heather, N. (2017). Q: Is addiction a brain disease or a moral failing? A: Neither. Neuroethics, 10(1), 115–124.

Jones, B. T., Corbin, W., & Fromme, K. (2001). A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction, 96(1), 57–72.

Koob, G. F., & Le Moal, M. (2008). Neurobiological mechanisms of addiction. Academic Press.

Kosten, T. R., & O’Connor, P. G. (2003). Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(18), 1786–1795.

Lamis, D. A., Malone, P. S., & Jahn, D. R. (2014). Alcohol use and suicidal behaviors among adults: A synthesis and theoretical model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 302–317.

Marlatt, G. A., & Donovan, D. M. (Eds.). (2005). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

McLellan, A. T., Lewis, D. C., O’Brien, C. P., & Kleber, H. D. (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA, 284(13), 1689–1695.

Moos, R. H., & Moos, B. S. (2006). Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction, 101(2), 212–222.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2018). Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide (3rd ed.). https://nida.nih.gov/

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395.

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2018). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis (9th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Rehm, J., Mathers, C., Popova, S., et al. (2009). Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet, 373(9682), 2223–2233.

Saitz, R. (2014). Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(2), 124–131.

Tonigan, J. S., Miller, W. R., & Schermer, C. (2002). Atheists, agnostics and Alcoholics Anonymous. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(5), 534–541.

Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371.

White, W. L. (2014). Slaying the dragon: The history of addiction treatment and recovery in America. Chestnut Health Systems.

Zvolensky, M. J., Lejuez, C. W., Kahler, C. W., & Brown, R. A. (2006). Integrating behavioral medicine and substance abuse treatment. Springer Science & Business Media.

Leave a comment