By: Dr. Curtis Peterson

What Are Groups? In psychology and therapeutic contexts, a group is commonly defined as two or more individuals who come into personal and meaningful contact on a continuous basis (Forsyth, 2018). While groups can range in size and function, therapeutic groups typically consist of 6 to 9 members. This size allows for sufficient diversity and participation while maintaining manageability.

Although group therapy often focuses on groups of six or more, couples therapy is also considered a form of group treatment. Many of the same group dynamics and facilitation techniques apply, including the creation of shared goals, exploration of interpersonal interactions, and the development of communication skills (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020).

Groups vs. Teams Teams are a structured subset of groups. While both involve collaboration, teams have clearly defined roles and objectives. Group therapy, in contrast, encourages shared responsibility among equal-status members (Levi, 2020). In group therapy, all members contribute equally to the process, unlike teams, where individuals are assigned distinct roles such as leader, scribe, or spokesperson.

Group Size and Its Impact The ideal size for therapeutic groups is between six and nine members. Fewer than six can result in limited interaction and weak group cohesion, while more than nine often leads to disengagement or an impersonal classroom-like setting (Corey, Corey, & Corey, 2018). Group size directly affects cohesion, participation, and individual contribution.

Therapeutic Power of Groups Group therapy is especially effective for individuals facing mental illness, addiction, or trauma. These individuals often experience isolation, and a well-facilitated group can reduce feelings of loneliness by demonstrating shared human experiences (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020).

Benefits include:

- Realizing one is not alone.

- Hearing others’ similar experiences.

- Building a sense of connection and understanding.

Facilitators must ensure the group does not evolve into an “enabling group,” especially in addiction treatment. When members romanticize substance use, research shows an increased risk of relapse post-session (Tucker et al., 2016). Facilitators must redirect conversations toward healing and recovery.

Social Loafing in Groups Social loafing occurs when individuals exert less effort in a group setting, especially when attendance is mandatory (e.g., court-ordered treatment). To mitigate this, facilitators can:

- Make individual contributions identifiable (e.g., weekly check-ins).

- Emphasize the value of each person’s input.

- Maintain an optimal group size (6-9 members).

Types of Group Interdependence

- Pooled Interdependence: Members contribute independently (e.g., each shares a personal story).

- Sequential Interdependence: Tasks are performed in sequence, with each step building upon the last (e.g., staged role-play).

- Reciprocal Interdependence: Members depend on each other for feedback and insight (e.g., sharing relapse stories and receiving reflections).

Avoiding Direct Advice While peer support is essential, direct advice can feel prescriptive. Instead of “You should…,” facilitators should encourage phrasing like, “In my experience, I found that…” This supports a more individualized and less directive approach (Corey et al., 2018).

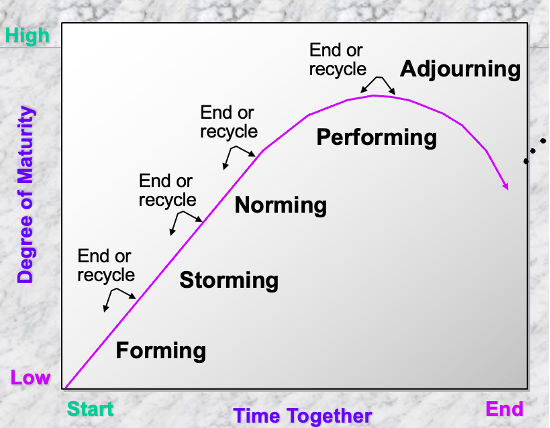

Five Stages of Group Development Adapted from Tuckman’s model (1965), groups typically progress through five stages:

- Forming: Introduction, orientation, and rule-setting. Facilitators work to reduce anxiety and build safety.

- Storming: Conflict and role negotiation. Dominant members may emerge; facilitators manage dynamics.

- Norming: Group cohesion begins. Members start to self-regulate behavior and internalize group norms.

- Performing: Active engagement in therapeutic work. Members apply strategies and support one another’s growth.

- Adjourning: Disengagement occurs as members grow independent. Facilitators support closure and transition.

Research has shown that individuals with psychopathic tendencies may not benefit from group therapy and may manipulate others, increasing risk for harm (Salekin, 2002).

Cohesion and Its Impact Cohesion refers to the loyalty members feel toward the group and the process (Forsyth, 2018). It influences:

- Participation: More cohesion typically increases active involvement.

- Conformity: Group norms are reinforced; excessive conformity may limit individual expression.

- Goal Accomplishment: Cohesion can motivate goal attainment but may shift focus toward maintaining group harmony instead of progress.

Determinants of Cohesiveness

- Group Size: Smaller groups have higher cohesion; large groups often lose intimacy and focus.

- Diversity: Diversity of experience enhances insight and problem-solving.

- Group Identity: Naming the group or creating a symbol enhances shared purpose.

- Success: Celebrating achievements reinforces unity.

The Dark Side of Empathy Facilitators must practice active listening rather than rushing to soothe. This approach fosters true understanding and prevents emotional avoidance (Neff, 2011).

Additional Factors

- Common Goals: Aligning objectives in diverse groups (e.g., voluntary vs. mandated participants) promotes unity.

- Group Success: Recognizing collective progress enhances cohesion.

- Status Differences: Facilitators must address perceived hierarchies within the group.

- External Threats: Outside influences can affect group trust and should be processed thoughtfully.

Groupthink Groupthink is a risk when cohesion suppresses dissent. Asch’s conformity experiments (1951) demonstrated how individuals may abandon personal judgment under group pressure. Facilitators can counteract this by encouraging dissent, assigning devil’s advocate roles, and validating individual perspectives.

Managing Conflict Conflict is natural and can be productive. Productive conflict fosters insight; personal attacks must be redirected to maintain safety. When conflict escalates, restructuring the group may be necessary (Yalom & Leszcz, 2020).

Adjourning and Closure Groups dissolve for various reasons: scheduled completion, natural disengagement, or unexpected turnover. Facilitators should:

- Celebrate progress

- Provide certificates or tokens of accomplishment

- Offer symbolic closure (e.g., a final group meal)

Cultural Considerations Cultural values shape group behavior. Collectivist cultures (e.g., Native American, Japanese) value unity and harmony, while individualist cultures (e.g., U.S., UK) prioritize autonomy. Facilitators should honor both perspectives in group processes (Triandis, 1995).

Conclusion Facilitating group therapy demands awareness, flexibility, and cultural competence. Effective groups balance cohesion with individual growth, manage conflict constructively, and navigate the complexities of human interaction.

References Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgment. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men (pp. 177-190). Carnegie Press.

Corey, G., Corey, M. S., & Corey, C. (2018). Groups: Process and practice (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Forsyth, D. R. (2018). Group dynamics (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Levi, D. (2020). Group dynamics for teams (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion: The proven power of being kind to yourself. William Morrow.

Salekin, R. T. (2002). Psychopathy and therapeutic pessimism: Clinical lore or clinical reality? Clinical Psychology Review, 22(1), 79–112.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Westview Press.

Tucker, J. A., Foushee, H. R., & Simpson, C. A. (2016). The impact of group process on treatment outcomes: Evidence from substance abuse group therapy. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 25–30.

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2020). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (6th ed.). Basic Books.

Leave a comment