By Dr. Curtis Peterson

Introduction Mate selection is a fundamental aspect of human social behavior that is influenced by evolutionary, psychological, and cultural factors. While biological imperatives drive reproductive success, cultural norms and social expectations shape how individuals perceive and pursue romantic relationships. This chapter explores the cultural dynamics of mate selection, the psychological underpinnings of attraction, gender differences in relationship goals, and factors that contribute to healthy romantic partnerships across diverse societies.

Mate Selection and the Role of Attraction Attraction is the initial phase that often precedes mate selection. While attraction can apply broadly to many individuals, mate selection typically involves narrowing one’s focus to a specific partner. The intention in mate selection often includes long-term bonding, emotional connection, and family creation (Buss, 1989).

Cultural Themes in Mate Selection Three major cross-cultural patterns are evident in mate selection:

- Mere Exposure Effect Zajonc (1968) coined the term “mere exposure effect” to describe the phenomenon that repeated exposure to a person or stimulus increases our preference for it. In the context of mate selection, this often means individuals form romantic relationships with those they frequently encounter—neighbors, coworkers, or classmates (Montoya, Horton, & Kirchner, 2008). Traditionally, most people married individuals who lived within close geographic proximity, typically within a few blocks. However, with the emergence of online dating, proximity is no longer a strict requirement. Despite this shift, individuals still tend to be attracted to those with similar social media algorithms and interests (Backstrom & Kleinberg, 2014).

- Similarity in Mate Preferences Assortative mating refers to the tendency for individuals to pair with others who are similar to themselves in characteristics such as intelligence, religion, values, and physical attractiveness (Watson et al., 2004). Cultural norms often shape what is considered “similar enough” to be compatible. Even when partners appear physically mismatched, research suggests their levels of perceived attractiveness tend to be equivalent within their social context (Lee, Loewenstein, Ariely, Hong, & Young, 2008).

- Equitable Distribution of Resources Across cultures, people seek fair distribution of resources within relationships. These resources may include emotional support, shared responsibilities, financial stability, and household contributions (Hatfield, Rapson, & Aumer-Ryan, 2008). What appears “fair” often varies between cultures, and fairness must be understood within the emotional and psychological dynamics of the couple.

Gender Differences in Mate Preferences Research consistently shows gender differences in mate selection. Buss (1989) found that men tend to prioritize physical appearance and youthfulness, while women prefer partners with status, earning potential, and ambition. However, the perception of potential—not just actual status—is also significant. Women may be attracted to ambition and long-term goals, even if those goals are unrealized (Eastwick & Finkel, 2008).

Power and Mate Preferences A feminist hypothesis suggested that as women gain financial and social power, their need for powerful male partners would decrease. Contrary to this hypothesis, research has shown that powerful women often seek even higher-status partners (Townsend, 1998). In contrast, individuals with less power are more likely to pursue equitable partnerships based on mutual contributions.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Relationship Goals Men across cultures show a greater preference for short-term, intense sexual relationships (Schmitt, 2003). In contrast, women typically prefer fewer but emotionally meaningful long-term partnerships. A notable experiment at the University of Hawaii found that 70% of men agreed to casual sex with a stranger, while 0% of women did (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). When asked about going on a date, approximately 50% of both men and women agreed, reflecting different motivations in short-term versus long-term relational interest.

Wealth and Serial Relationships Men with greater wealth are more likely to engage in serial relationships, a form of infidelity characterized by maintaining more than one romantic relationship simultaneously (Greiling & Buss, 2000). Additionally, men are more likely to commit to long-term relationships when perceiving premarital chastity in their female partners, which reflects persistent double standards regarding sexual behavior (Schmitt, 2005).

Infidelity and Status Dynamics in Women Cross-cultural studies reveal that women are more likely to engage in extra-pair copulation under two conditions: dissatisfaction in their primary relationship and the presence of a higher-status alternative partner (Gangestad & Thornhill, 2008). Women tend to “cheat up,” seeking partners of higher social or resource status. In contrast, men tend to “cheat down.”

Shifting Trends: From Resource-Based to Partnership-Based Relationships The industrial and post-industrial eras have shifted marriage from being resource-driven to partnership-oriented. In modern cultures, individuals seek partners for emotional companionship rather than financial necessity (Finkel, Hui, Carswell, & Larson, 2014). This trend disproportionately benefits women, who often thrive in emotionally supportive, egalitarian relationships.

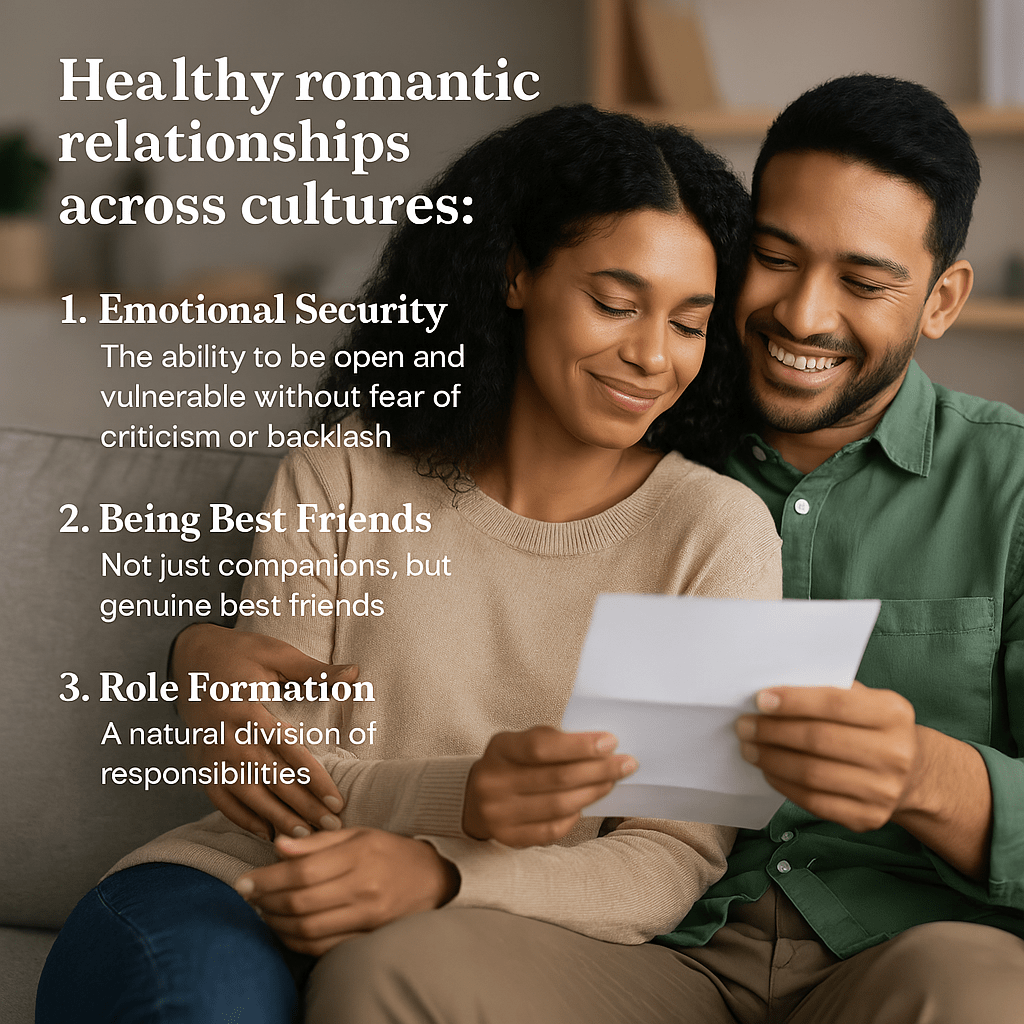

Healthy Romantic Relationships Across Cultures Despite differences in values and expectations, three components appear universally important for sustaining healthy long-term relationships:

- Emotional Security Healthy couples feel safe expressing vulnerabilities without fear of judgment or retaliation. Emotional security fosters open communication and deep trust (Gottman & Silver, 1999).

- Best Friendship Romantic partners who are also best friends report higher satisfaction and resilience. They share experiences, support each other’s growth, and reconnect quickly after spending time apart (Demir, Orthel-Clark, Ozdemir, & Valentine, 2015).

- Role Formation Successful couples often form natural divisions of labor based on strengths and preferences. In traditional relationships, roles may align with cultural expectations, but satisfaction depends on mutual agreement and acceptance (Amato, Booth, Johnson, & Rogers, 2007).

While modern Western cultures emphasize egalitarian roles, other societies may prioritize traditional gender-based roles. What determines relationship health is not the structure of roles, but whether individuals find them fulfilling and equitable.

Conclusion Mate selection and romantic relationship dynamics are deeply embedded in cultural, social, and psychological contexts. While certain preferences like kindness, loyalty, and emotional security are universally valued, the ways individuals select partners and define healthy relationships vary greatly across societies. Ongoing research continues to explore how globalization, technology, and shifting gender roles influence romantic behavior.

References Amato, P. R., Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., & Rogers, S. J. (2007). Alone together: How marriage in America is changing. Harvard University Press.

Backstrom, L., & Kleinberg, J. (2014). Romantic partnerships and the dispersion of social ties: A network analysis of relationship status on Facebook. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 831–841.

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), 1–49.

Clark, R. D., & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2(1), 39–55.

Demir, M., Orthel-Clark, H., Ozdemir, M., & Valentine, D. (2015). Friendship and happiness in the United States and Turkey. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(2), 245–267.

Eastwick, P. W., & Finkel, E. J. (2008). Sex differences in mate preferences revisited: Do people know what they initially desire in a romantic partner? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 245–259.

Finkel, E. J., Hui, C. M., Carswell, K. L., & Larson, G. M. (2014). The suffocation of marriage: Climbing Mount Maslow without enough oxygen. Psychological Inquiry, 25(1), 1–41.

Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (2008). Human oestrus. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275(1638), 991–998.

Gottman, J. M., & Silver, N. (1999). The seven principles for making marriage work. Crown Publishing Group.

Greiling, H., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Women’s sexual strategies: The hidden dimension of extra-pair mating. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 929–963.

Hatfield, E., Rapson, R. L., & Aumer-Ryan, K. (2008). Equity theory and relationships. In Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 411–424). Psychology Press.

Lee, L., Loewenstein, G., Ariely, D., Hong, J., & Young, J. (2008). If I’m not hot, are you hot or not? Physical attractiveness evaluations and dating preferences as a function of one’s own attractiveness. Psychological Science, 19(7), 669–677.

Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889–912.

Schmitt, D. P. (2003). Universal sex differences in the desire for sexual variety: Tests from 52 nations, 6 continents, and 13 islands. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 85–104.

Schmitt, D. P. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: A 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28(2), 247–285.

Townsend, J. M. (1998). What women want–what men want: Why the sexes still see love and commitment so differently. Oxford University Press.

Watson, D., Klohnen, E. C., Casillas, A., Simms, E. N., Haig, J., & Berry, D. S. (2004). Match makers and deal breakers: Analyses of assortative mating in newlywed couples. Journal of Personality, 72(5), 1029–1068.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 1–27.

Leave a comment